During the First World War the extensive catacombs underneath Arras were used by the military. They sheltered troops and provided a safe transit up to the forward areas. A field hospital was based here. Many surgeons operated on the wounded within these underground spaces. The catacombs offered protection from hostile artillery fire for both soldiers and civilians.

Trenches at Ypres

- These preserved trenches at the Sanctuary Wood Museum were the scene of bitter fighting. In October 1917, James Hadley a Sapper Officer wrote in his diary, ‘Of the terrible and horrible scenes I have seen in the war, Sanctuary Wood is the worst’.

The Men Who Planned the War (2016)

The staff of the British army have not had a good press. During the Allied victory celebrations there were few who chose to raise a glass to them. They have been seen as incompetent, ignorant and indulged. Their reputation tarnished by the high level of casualties. Soldiers sent to their deaths by uncaring bunglers who were cosseted in chateaux far from the fighting. But are these claims justified? Have we really taken a hard look at the evidence?

This book takes up the case for the staff. It argues that they did a professional job under challenging circumstances. The detailed and sometimes mundane work of the staff was not the stuff of which heroes were made. While there were mistakes, their successes were overlooked. They made a significant contribution to the war effort which has been overlooked. It is time the record was put straight.

A Lieutenant at Fifteen (2020)

Heads must have turned when a chauffeur driven Rolls Royce Silver Cloud pulled up in front of the War Office on a December morning in 1914.

The young man who stepped out was just over fifteen years old! Dressed in a black silk top hat, Alfred Davis looked older than his teenage years and must have cut an impressive figure. He was there to meet Sir George Arthur, personal secretary of Lord Kitchener, Secretary of State for War. Alfred wanted to obtain a commission to become an officer. If successful he would become one of the youngest officers in the British army.

This is the remarkable story of Alfred Davis. He survived two major battles and many months of trench warfare. Any lack of experience was more than outweighed by his extraordinary resilience.

How Alfred defied the rules and endured the ordeal of the Western Front is described in this article. ‘A Lieutenant at Fifteen’ published in the journal of the Western Front Association, Stand To No 117 (February 2020).

Tours to the Western Front

Owing to Covid 19, tours to the Western Front have been moved to 2021. The first trip planned is to Ypres from Thursday 13 May to Sunday 17 May. Other tours will follow once the situation becomes clearer.

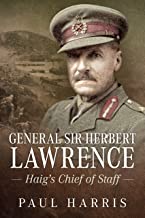

General Sir Herbert Lawrence, Haig’s Chief of Staff (2019).

As Chief of Staff to Field Marshal Sir Douglas Haig in 1918, General Sir Herbert Lawrence played a key role in the defeat of Germany in the First World War.

This biography traces his remarkable career and argues that he has a strong claim to be recognised as one of the principal architects of Allied victory. Described as ‘a man of outstanding ability both as a soldier and in business’, it is surprising that this towering figure has received such little attention.

He remains one of the forgotten figures of the war.